By: Aleksandra Grabowski, PhD student at Wageningen University

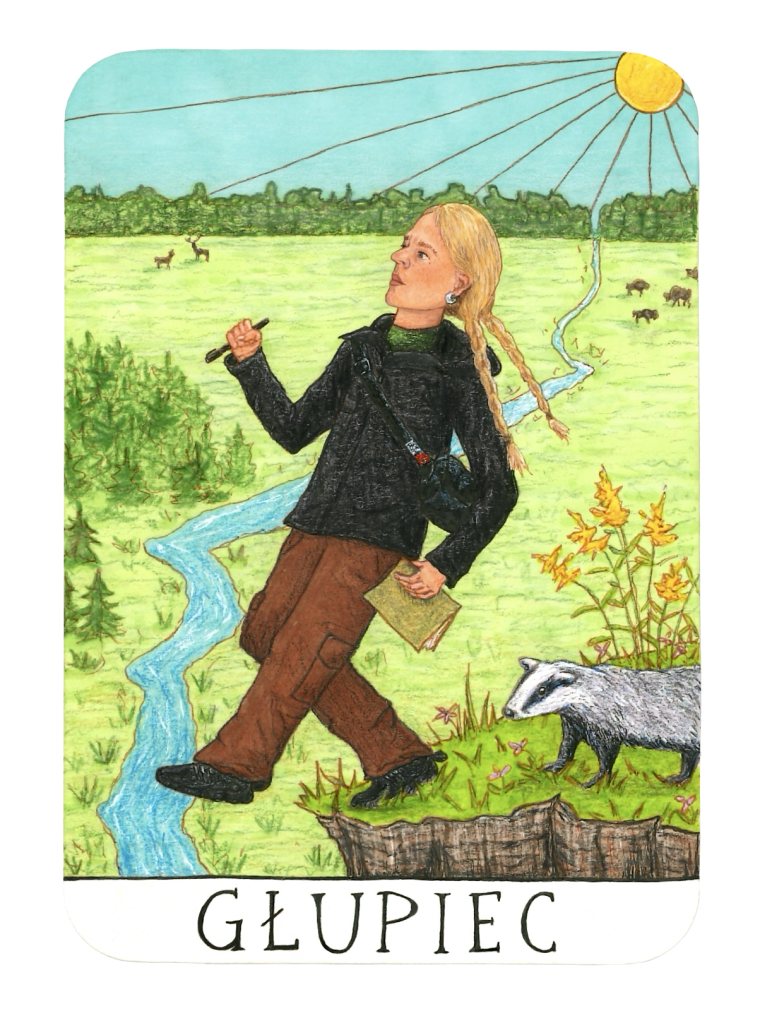

A worn stack of cards caught my eye, perched on a shelf across from the tiled woodburning kitchen stove that now just stored flame-licked pots and pans. I was renting this space that scraped the outskirts of Białowieża Forest and these weren’t my things. But something pulled me closer. Grey sunlight filtering thinly through the window shone not on a regular deck, but rather a set of tarot cards. I gave them a lopsided shuffle, flipping one up from the middle. The Fool glanced at me askew from his peripheral vision. He was a young, medieval-looking man, blissfully unaware that he was stepping off a cliff. I searched for the card online, getting hit with an AI summary I couldn’t dodge:

The Fool card represents new beginnings, spontaneity, adventure, or a leap of faith

into the unknown. It can also indicate recklessness, naivety, or fear of starting something.

Okay, dang. That did resonate. It was the first of my days “in the field” on the northeastern edge of Poland. I had been stumbling through daily interactions, tongue veering hastily around Polish. My vernacular was partially trapped in the 1988 farmlands my parents had immigrated from, yet also peppered with the grammatical dissonance of my own Chicago diaspora. My mind raced with questions about what it really meant to “do” ethnography. None of the methodology texts read in a grey office a thousand kilometers away made sense anymore.

Was I still on the cliff or over it? Or, following the line of “My life is a field note. I am a field note,”1 had I always been over the edge? With every observation of the world, with every breath taken being some kind of ethnographic deciphering? Maybe we are indeed forever teetering with one foot on the ground and one dangling off. Floating through the ever-shifting liminality of a PhD process, of a forest, of life itself.

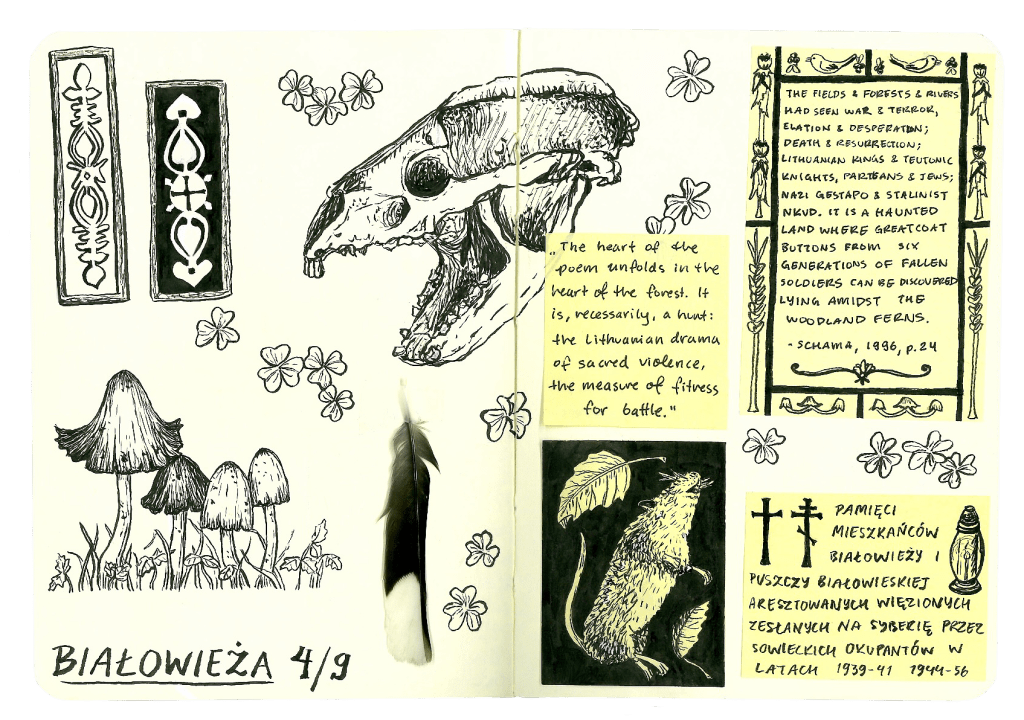

It felt like Białowieża Forest had been on the lips of every other researcher I met since I first moved across the Atlantic. Dense piles of peer-reviewed articles, books, and newspaper headlines brandishing its name flashed out at me, an endless stream of stories and insights and concerns. It would be a lifetime of reading to parse through it all. Who was I to come here? An artist living in the area who I spoke to over a scratchy video call months earlier told me how many years it took her to finally feel like she knew Białowieża Forest. And of the many artists who come and go, hoping to make a project about the forest in a few short weeks. Las się śmieje wtedy, she said. “The forest laughs then.” How was I doing anything different, I thought— was the forest laughing at me now? And what does it mean to know a forest?

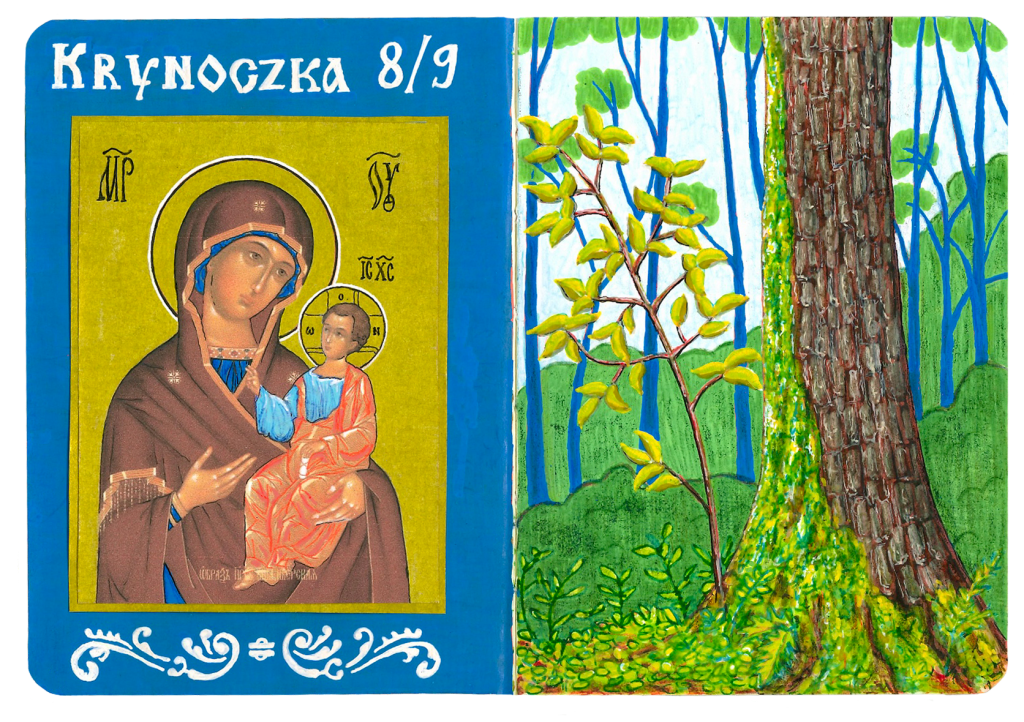

Over the next weeks I wandered along trails while peering at mushrooms and drying streams, ate steaming soup offered graciously in homes by the flickering light of stories about too-close bison encounters and neighborhood tensions. My eyes traced the gold trimmings of church interiors and I was encircled by the bellows of red deer carried across the chilled night air. I felt the thrum of resin within 100-year-old pine log walls that had survived being hurriedly unfitted, transported, and refastened into worn grooves over multiple waves of exodus. And it felt like I was constantly in the middle of everything. Is it just “the field,” is it just “home,” or is it axis mundi, the uncontested center of the world that everything else melts into murk outside of?2

I don’t think I answered any of my questions. Perhaps I never will. And even if I do, I’ll get it wrong. I know I will. But I think every researcher does. So in the meantime we must learn to enjoy the ride, slowly absorbing the sharp grids and soft curves of enforested paths and watching saplings emerge from the leaf litter, laughing and holding back tears over shared cups of tea, and scribbling away in our notebooks both in and out of the field (if there is such a place).

1: p. 133 in Schütt, Morten. 2020. “Life notes: When fields refuse to stay in place.” In Anthropology Inside Out: Fieldworkers Taking Notes, edited by Astrid Oberborbeck Andersen, Anne Line Dalsgård, Mette Lind Kusk, Maria Nielsen, Cecilie Rubow, and Mikkel Rytter, 115–33. Canon Pyon, UK: Sean Kingston Publishing.

2: For more on this notion, see Primeval and Other Times by Olga Tokarczuk

Leave a comment